A Different Kind of Camping Part II: My First Days

I arrived in Zaatari, the Syrian refugee camp in Jordan, at about 10 in the morning to start my volunteer work. It was cold, and the rain from the night before had turned the camp into a muddy mess. [metaslider id=3112]

While I was stopped at the gate, I was accosted by a group of boys, ranging from about 6 years old to 20. They grabbed my camera, tried to open my bag and get money, and even though they were laughing, they managed to frighten me a bit. The situation became slightly more alarming when the oldest boy in the group gathered all six of his friends around me so I could take their picture. It was definitely an exciting start to my morning.

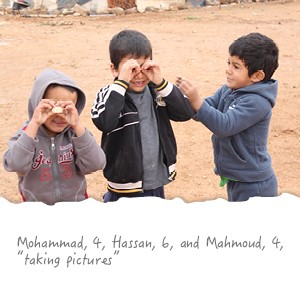

Outside Zaatari, among the undocumented Syrian refugees’ tents and shanties, several children saw me taking pictures while they were playing. They ran over and asked me to photograph them. While I was taking pictures and letting them (very, very carefully) photograph each other, their mothers deemed me trustworthy enough to let me talk to them. The families I met not only opened their homes to me, they opened their hearts and told me about their harrowing experiences with an honesty I will never forget.

On the Outside Looking In In Jordan, refugees fall into several categories, even when they come from the same place. There are refugees inside the camps and refugees in the urban environment. Refugees can have legal documentation, or they were forced to sneak in when Jordan closed its borders to them in 2015.

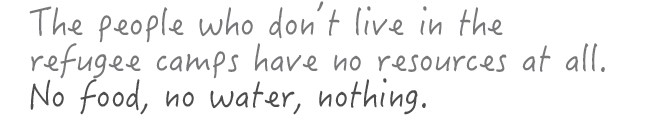

The treatment of refugees inside vs. outside Zaatari is vastly different. Inside Zaatari, I found that although the people do not have money, and problems abound, at least some of the burden is alleviated by the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Needs like food, water, and heat are more likely to be met. Conversely, the people who don’t live in the refugee camps have no resources at all. No food, no water, nothing.

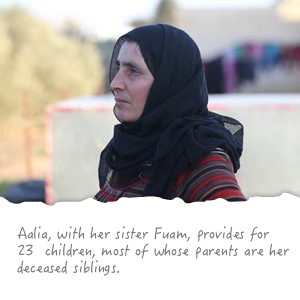

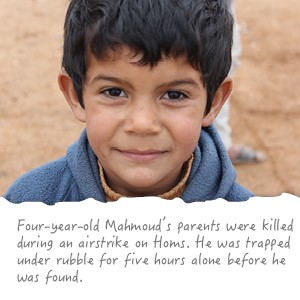

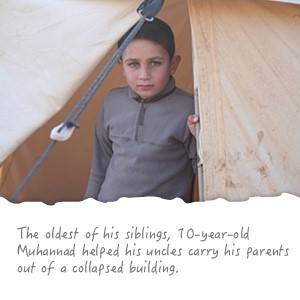

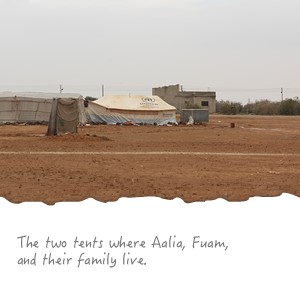

While the children scurried around, asking me to watch them play hopscotch, their mothers (two sisters  named Aalia and Fuam who traveled here with their husbands) told me about a recent snowstorm and its aftermath, their experiences in Syria, and problems they’ve had with health care delivery in Jordan. Not only do they have their own children, but they are also caring for the children of their two brothers, who passed away in Syria along with their wives and some of their other children when a building collapsed in Homs. These two mothers are raising 23 children between them, including a 4 month old.

named Aalia and Fuam who traveled here with their husbands) told me about a recent snowstorm and its aftermath, their experiences in Syria, and problems they’ve had with health care delivery in Jordan. Not only do they have their own children, but they are also caring for the children of their two brothers, who passed away in Syria along with their wives and some of their other children when a building collapsed in Homs. These two mothers are raising 23 children between them, including a 4 month old.

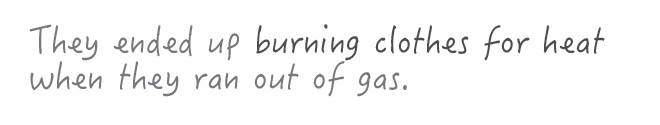

During the snowstorm, while refugees in Zaatari received blankets and propane, the 150 undocumented people outside the gates got nothing. They weathered the storm without heat (the nights here get incredibly cold) while the snow soaked through their tarps and turned the ground beneath them into a pond, which then proceeded to flood their tents. They ended up burning clothes for heat when they ran out of gas, and they weren’t able to purchase more until three days after the storm.

When asked how they could afford the gas, the women explained that they planted and sold tomatoes and cucumbers during the summer. Their husbands, an engineer and a pharmacist, pooled their resources, invested in sheep, and sold milk to residents of Zaatari (where they are technically not allowed to enter). They also relied on assistance from an aunt in Jordan, who passed away a month after their arrival. Somehow these efforts have managed to feed 30 mouths.

I also asked them why they wouldn’t try to live in the camp, especially after they told me their lives would be easier. Aalia explained that once Syrians decide to call the camp home, they are not allowed to leave. She and her family wanted the freedom to travel and move farther inland if possible. That was a year ago. The families have since decided that they will put their efforts into creating a new life in Zaatari, claiming they won’t be in poverty forever. I sincerely hope that’s true.

The Ties that Bind Watching the interactions between the two sisters and the children, I had no idea which ones belonged to whom, until it was pointed out. Naturally, I’m not sure what the family dynamic is like when I’m not there, but I did notice that the fathers disciplined the kids equally with slaps on the back of the head for talking during two of the recorded interviews. Even though I will have no idea what’s normal until they become comfortable around me, I do hope the tenderness these two mothers showed the children is a daily occurrence, especially for those who lost their parents in Homs.

The mothers told me about various health problems for which they cannot get assistance. Several of the  kids had upper respiratory infections, and some, especially the smaller children, had difficulty breathing. Though there are doctors inside the camp, these people don’t have access to them, and they have to walk several kilometers to get to the nearest emergency room, which they must pay for themselves. I give what medical advice I can when they ask, which is to drink hot tea.

kids had upper respiratory infections, and some, especially the smaller children, had difficulty breathing. Though there are doctors inside the camp, these people don’t have access to them, and they have to walk several kilometers to get to the nearest emergency room, which they must pay for themselves. I give what medical advice I can when they ask, which is to drink hot tea.

After long conversations about their children, and their lives, the mothers began to openly talk among themselves (and to me) about living in Homs. They spoke mostly of fear, which existed even before the Arab Spring began in 2011.

Exercises in Futility Though the magnitude of the refugees’ needs vary inside and outside Zaatari, I was struck  by how so many of the projects I work on fail to address these groups. The Jordanian government leaves these people out to dry, and I’m realizing more and more that even though resources are abundant, the combination of attitudes toward the Syrian refugees and bureaucratic barriers put in place by the Jordanian government makes these resources difficult for people in Zaatari to access, let alone the undocumented Syrians.

by how so many of the projects I work on fail to address these groups. The Jordanian government leaves these people out to dry, and I’m realizing more and more that even though resources are abundant, the combination of attitudes toward the Syrian refugees and bureaucratic barriers put in place by the Jordanian government makes these resources difficult for people in Zaatari to access, let alone the undocumented Syrians.

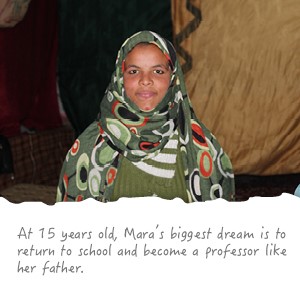

I spoke to 15-year-old Mara, who had not been to school in over a year. Despite her background (her parents are a college professor and a nurse), she has no hope of attending university. Her father sells black market goods in Zaatari, but otherwise, she and her family have no means of earning money. I asked her if she had heard about the women’s empowerment projects here, specifically ones geared toward the continued education of young women. She replied, “What’s the point? We can’t leave the camp to go to university anyway.”

Because of laws that Jordan has in place regarding international students, it’s almost impossible for Syrians to attend Jordanian universities. None of these students have exit permits from Syria, which seems like a completely arbitrary requirement from the Jordanian Ministry of Education.

Even my mobile clinic project, which aims to provide screenings for secondary diseases, makes no sense considering there’s an entire population without access to primary care. After talking to my boss, Simon, I realized how many hoops NGOs jump through to stay on the Jordanian government’s good side. Simon explained, “If the Jordanian government doesn’t want us to address them, we can’t address them sustainably. We need to use our resources to reach the people we can help.” This attitude seems slightly defeatist to me, like even the UNHCR has turned its back on the people who need it.

I asked Andy Harper, the UNHCR country rep in Jordan, how we can ignore such a significant population  who lives right outside the camps. He told me that, unlike the Palestinians years ago, Jordan’s policy regarding the Syrians doesn’t include integration. Harper used the phrase “emergency situation” to describe the Syrians since the Jordanian government considers them a risk and is only focusing on maintaining their basic needs while channeling other resources into the Jordanian public, which does not include the Syrians. The general attitude is that addressing the undocumented is a waste, when by comparison, 1.25 million documented Syrians who the UNHCR can and should help are in Jordan right now. I can’t deny the good work that the UNHCR does, but to me, it doesn’t change the fact that people who still need help aren’t receiving it.

who lives right outside the camps. He told me that, unlike the Palestinians years ago, Jordan’s policy regarding the Syrians doesn’t include integration. Harper used the phrase “emergency situation” to describe the Syrians since the Jordanian government considers them a risk and is only focusing on maintaining their basic needs while channeling other resources into the Jordanian public, which does not include the Syrians. The general attitude is that addressing the undocumented is a waste, when by comparison, 1.25 million documented Syrians who the UNHCR can and should help are in Jordan right now. I can’t deny the good work that the UNHCR does, but to me, it doesn’t change the fact that people who still need help aren’t receiving it.

Coming up in Part III: I delve into my experiences addressing Syrian refugees’ most severe health care needs.

The views, opinions, and positions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or positions of CDPHP®.

The Daily Dose

The Daily Dose

Comments are closed.